On Seven Acres in Macy: Roots run deep on Umonhon Nation Public School’s III Sisters Farm

On Seven Acres in Macy: Roots run deep on Umonhon Nation Public School’s III Sisters Farm

By Tyler Dahlgren

The sun beats down on the seven-acre farm beyond the south endzone of Wade Miller Stadium, the home and headquarters of Umonhon Nation Public School’s III Sisters Farm to School Program.

It’s one of those sultry dog days of summer, the heat is inescapable, and, for a fleeting moment, Wakeen Teboe thinks about calling it quits. Air conditioning is alluring during these kinds of scorchers, but the sophomore-to-be set a goal at the summer’s onset of saving $2,000, and around the rolling hills of the Omaha Reservation they don’t make a habit of giving up.

The fleeting moment passes, and Teboe, one of 40 or so students employed to farm the land last summer, gets back to work.

“I learned to not listen to my mind when it wants to give up,” said Teboe, who eclipsed his goal last summer and saved nearly three grand when it was all said and done. “The garden helped me make more friends and I was able to help my mom out with some of the bills. I pushed through, even when I felt like quitting.”

The seven acre farm in Macy is the first of its kind, a bountiful slot of land where they’re growing everything from cabbage to blue corn and every herb and spice you can think of in between. It’s surreal really, how fast it all came together, and though there’s little time to reflect (starter plants are eagerly waiting to be planted in the school’s greenhouse), it’s a fun story to share for the innovatively bold folks who brought so much life to this land. In doing so, they brought this land to life, and reconnected a generation of students with their past.

“When you see our kids down there, showing up before eight o’clock to work in a hundred degree heat and enjoying it and coming back the next day and clocking in, that’s why we do it,” said UNPS superintendent Stacie Hardy.

The III Sisters Farm to School Program's roots live in Dr. Brenda Murphy's outdoor classroom, which introduces students to the essentials.

"She teaches them about soil health, soil dynamics, plant health, plant relationships, those types of things," said head maintenance supervisor Richard Valentino, one of the key cogs in the III Sisters machine. "From her, the students learn that more holistic foundation of it. We're really starting to notice that our freshmen and sophomores last year that had the opportunity to go through Dr. Murphy's class were able to be engaged in the garden pretty seamlessly."

The garden started a handful of years ago with a group of JAG Nebraska students and a challenge.

“They were tasked with coming up with a project that would provide employability for them while also giving back to the community,” Hardy said. “With the high rate of diabetes and heart disease throughout the community, the students wanted to do something to help the health of the Omaha people, and they came up with the idea of a garden where they’d grow and then sell fresh produce.”

To understand the significance of what the farm’s given to UNPS students, you first need to understand their circumstances. Employment opportunities in Macy are scarce to completely non-existent. There’s a gas station that carries groceries, but the other two retail stores in town, the Chief Store and Bluestem Coffee House and Cafe, are housed in, and operated by, the school.

“There’s no free market in the community,” said Valentino. “There’s no mom-and-pop shops, nothing like that.”

The students brought their idea to the Omaha Tribe, who saw the vision and leased the district the land beyond the football stadium. The district partnered with the Nebraska Department of Labor, Nebraska Game and Parks and a host of others and the farm has been blossoming ever since. In the summers, students work four hour shifts, Monday through Friday.

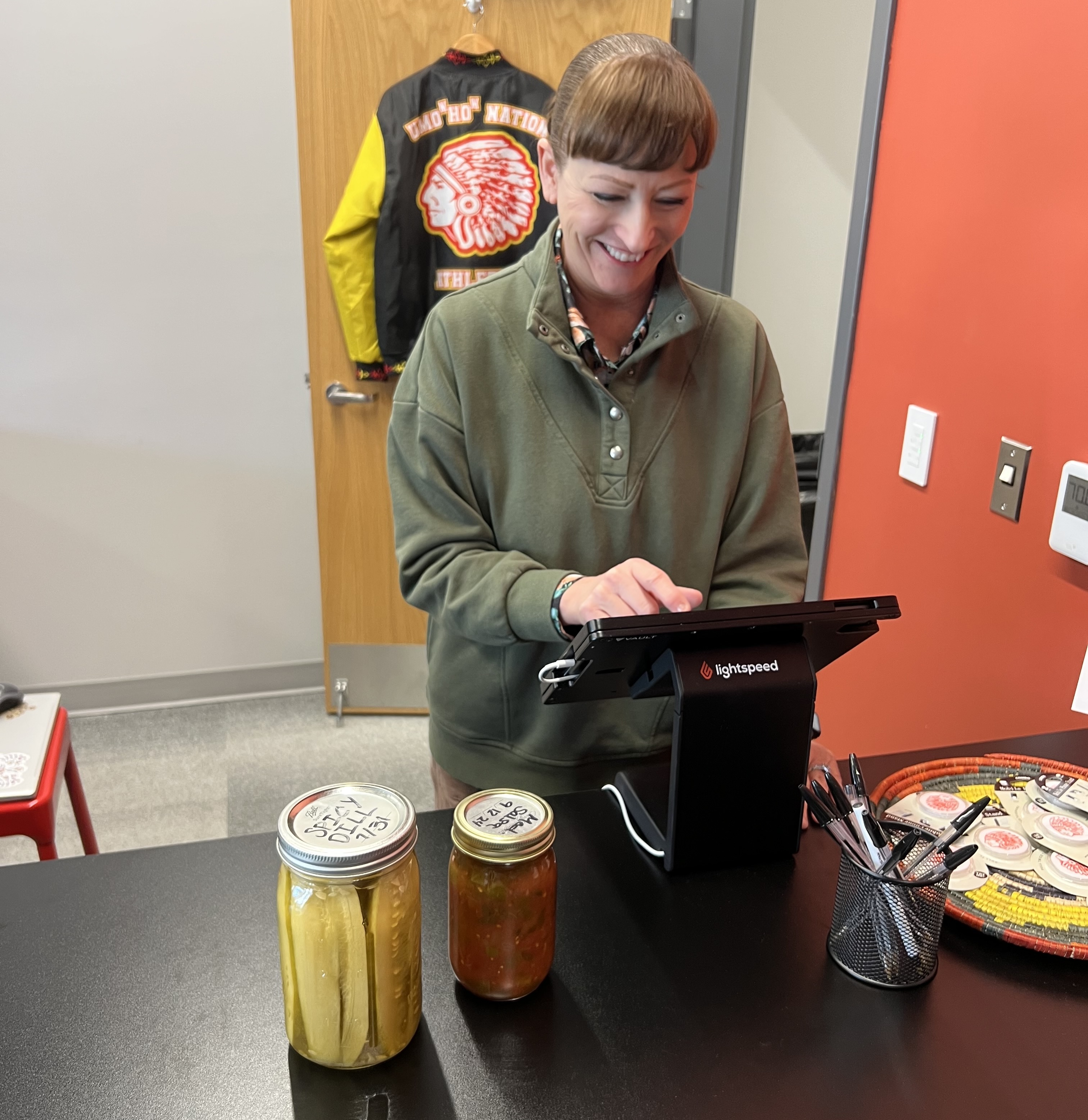

“They run a farmer’s market and we also bring fresh produce into the school cafeteria for the salad bar and for the coffee shop, so there’s a connection there with our culinary pathway,” Hardy said. “After the produce is harvested it goes through their department downstairs, and that’s where students learn to can and pressure cook and clean. They make bread, jams, salsas, you name it. There’s a sense of belonging that comes with it, a sense of community and the satisfaction of being able to give back.”

The farm is divided into sections. On a big table in the conference room on the second floor of UNPS, Valentino lays out a massive map and starts pointing. Watermelons, pumpkins, choke cherries and elderberries, everything has its spot. And they grow everything. There’s a composting area and, in the near future, a trail that’ll make it easier to navigate the area.

“We have the farm in a secluded area, so there’s not a limelight on it day to day, which is a good thing to us,” said Valentino, who noted the students tend to perk up a little bit when visitors do swing by. “They play the role. When we have potential investors or different organizations come in, they work a little extra hard and it’s like, ‘Hey, we want ‘em to see this. We want ‘em to really know what this is.’”

The students, having been given an introduction to soil dynamics and plant health at a young age in Dr. Murphy’s outdoor classroom classes, have taken ownership of the farm. They’re introduced to the curriculum as kindergarteners. It’s one of their special rotations, explained Hardy, no different than P.E. or art.

“It is awesome,” said Valentino. “There’s nothing better than seeing that.”

It’s a source of pride and a connection to the history of their people. At the beginning of the planting season, an elder visits the group to lead a prayer and to share stories from the tribe’s past. It’s a young but sacred tradition. The Omaha Tribe passes on wisdom and practice verbally, through storytelling. They don’t write anything down, hence the importance of an elder’s visit.

“Without this vision, without this garden, a lot of our kids wouldn’t be able to come by those teachings that, for a long time, were passed on from generation to generation,” said Valentino.

Macy is considered a food desert, and before UNPS launched the III Sisters project fresh and healthy food wasn’t necessarily easy to come by. Those days are gone. Students and their families are becoming measurably healthier. Some have even taken starter plants home to grow their own backyard gardens.

“Gardening, planting, when to harvest certain plants and to water and care for them, those are all things I’ve learned working on the farm,” said sophomore Emilie Lyons, who was able to put a good chunk of change in a savings account for college. “I like the idea of being on a team. Not everyone works the same, and that’s okay, but I know how I like to do things and how I like to be a part of a team.”

When the students arrive on site, they tuck their phones away and essentially step back in time. For four hours, it’s just them, the crops, and, if they’re lucky, a cool breeze here and there.

“To see the kids come in and automatically hand their phone to their regular accumulator and go off with their group, it’s pretty neat,” said Valentino. “I’d see a group of four girls who didn’t really communicate on a daily basis, but when they got out there in the garden they started laughing and talking and pulling weeds and doing a great job. You can’t put a value on that. That’s what it’s all about.”

In less than five years, the farm has proven its sustainability and its value in Macy's quest towards food sovereignty.

“Our plan to make the most impact for these kids is to build a processing center that would provide this access to nutrition to our families year round," said Hardy. "The search for funding to make this dream happen has just begun and UNPS needs your help to keep moving forward.”

Above all, Hardy is proud of the vision her team shared and the devotion that’s been required to pull it off. It’s the passion of people like Valentino, who takes care of the entire building and the grounds around it and still pours countless hours into the farm because he knows how powerful an opportunity can be, that stokes the flame.

“I’m all in,” Valentino said. “I love it for the kids. I’m all in for the kids.”

The students take it from there.

“This is the first project in Indian country that has been to this scale and provided employment for students, so we take them with us when we present at the national conferences and they’re able to tell the story,” said Hardy.

“We truly feel like this is their story to tell.”

Their story, on their seven acres.