To Tell You the Truth: Riverside’s homegrown educators help bolster school’s strong culture

To Tell You the Truth: Riverside’s homegrown educators help bolster school’s strong culture

By Tyler Dahlgren

The Cedar River flows just to the west of a 20-mile stretch of Highway 52 that connects Spalding and Primrose down to Cedar Rapids and Belgrade . With campuses in the former and the latter, Riverside Public Schools superintendent Steph Kaczor knows this winding road like the back of her hand.

Kaczor isn’t from here, but these communities and this school district, which just celebrated the 10-year anniversary of its consolidation, have become home. Celebrating a consolidation? Those two words belonging in the same sentence is a conundrum in itself.

But at Riverside, under Kaczor’s leadership, they’ve decided to embrace who they are now while holding on to who they were back then. Kaczor, who first came to Spalding Public School in 2005, doesn’t see the point in doing it any other way. From Spalding to Primrose down to Cedar Rapids and Belgrade, they’re in this together.

They are Riverside.

“I love the people, and a lot of places would say that their school has a family feel, but it’s real here,” Kaczor, a Chambers native who first student taught in Bartlett while earning her education degree from Mount Marty University in Yankton, said. “That’s one thing we still take pride in. When someone hurts here, we all hurt. These kids are everyone’s kids. We cover for each other so much and are so invested in our lives inside and outside of school. We’ve carried that on since becoming Riverside, and it’s why this is such a special place.”

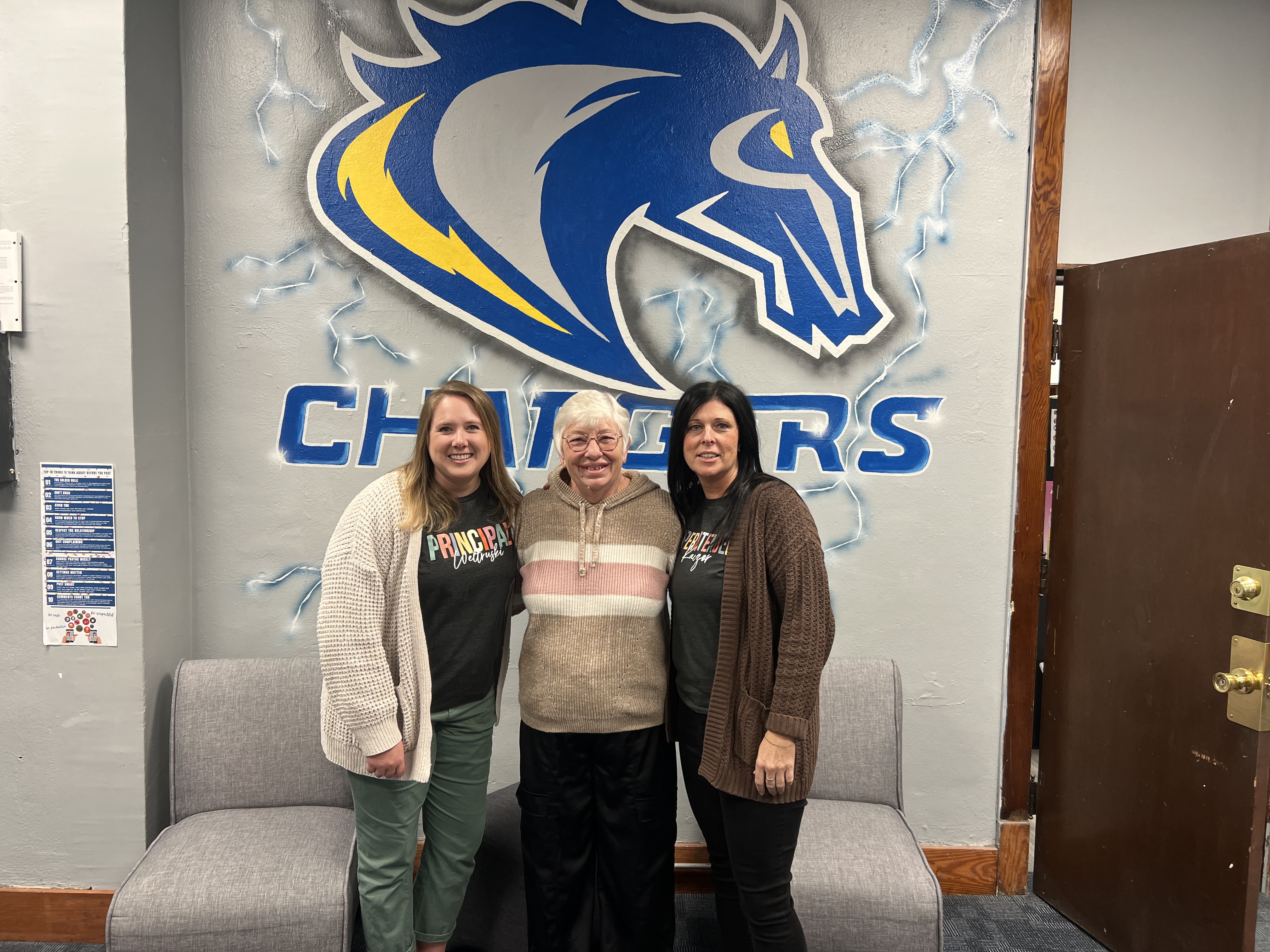

Of Riverside’s 31 teachers and administrators, seven are quote unquote “homegrown”, meaning they’ve never worked anywhere else. Three of the seven, including 4th and 5th-grade teacher Julie Rankin (Spalding Class of 1989), Cedar Rapids site principal Tricia Martinsen (Cedar Rapids Class of 1993) and special education teacher Kim Webb (Spalding Class of 1995), are alums. They’re Riverside, through and through.

“I have a very vested interest, not only in my community, but in this school,” said Martinsen, a longtime paraeducator who began teaching full time at 40 and is now in her second year as a principal after being encouraged by Kaczor to go for a master’s degree. “I am from here. My mom worked here. She was a janitor and a lunch lady. I have so many long-lasting memories of this place that have defined who I was and who I am.”

This is year 22 for Rankin, who said the building in Spalding looked a whole lot different in the eighties, back when the front doors to the school were kept unlocked and when there was only one gymnasium, the infamous “Cracker Box.” She’s proud to teach in the school she attended, and the more things change, the more they stay the same.

“There’s always been a supporting, family-like culture here where it doesn’t matter if the kid is in your room or so-and-so’s room,” Rankin said. “They’re all our kids, and we are all invested in supporting them the best we possibly can.”

The building may look different, but it still holds warm memories for Rankin. She hopes her students will look back on their time in fourth and fifth grade at Riverside and feel that same warmth.

“I hope they remember having fun while learning and creating fun memories,” she said.

The daughter of a teacher, Webb always had an educator’s inclination, though she was initially swayed outside of the profession. Well, all the way to Early Childhood, which back then wasn’t officially considered “teaching”, at least. She lived in New Mexico, where her Texan husband worked, and had two children. The eldest has autism, and as she got closer to school-age, the Webbs knew they needed to make a move.

“I knew the education systems there and here very well,” Webb said. “I wanted my autistic daughter to get a quality education, and I knew Nebraska was the place for that.”

They listed their house in New Mexico, it sold in nine days, and the Webbs moved to Greeley County in 2016. Webb started substitute teaching that year, and became the district’s K-12 special education teacher in 2017.

“It’s just very family-oriented, both from the staff side and the parent’s perspective,” she said. “It’s small town values. Everybody knows everybody’s kids, so they’ll invest a little more into the students because of those relationships. It’s not just a number or a name. They know these kids. They know their backgrounds and their families.”

Sixteen years ago, Melissa Weltruski had never heard of Spalding, Nebraska when she accepted her first full-time teaching position in the small town on the southern edge of The Sandhills. A 2005 graduate of Sidney High School, Weltruski earned her teaching degree from Chadron State before subbing for a year at Ogallala. She remembers her first impressions of Spalding vividly.

“I’ll never forget, it was really early so I was kind of driving around the town and I pulled over alongside a fenceline and called my mom,” Weltruski said. “I was like, ‘Mom, this town is really, really small. I don’t know if I can do it.’ But once you meet the people here, and once you become accustomed to the vibes here at school, it all kind of clicks and you realize how special of a place it is.”

She needed a job, and that’s exactly what Kaczor and then superintendent Alan Ehlers offered that day. Weltruski, who grew up knowing she was going to teach, accepted the position with an open mind and a good attitude. She coached volleyball and taught social studies before spending nine years as the district’s technology coordinator.

Weltruski never planned on becoming an administrator, but Kaczor saw her leadership qualities and encouraged her to take the next step. She was a member of UNK’s first Next Gen Leadership Academy cohort, and the 2024/25 school year is her first year as a principal.

It’s tough to leave a place when there’s so many people there who believe in you, she’s learned.

“My goal was to stay for three to five years, get that experience and then go back to Western Nebraska or Wyoming,” Weltruski said. “But I’ve stayed because of the people. Our community members are great. We have great teachers who see something that needs to be done and they do it. Our classified staff, I mean, it’s truly just a team effort. Our school board members are great, and the administration works well together. People have believed in me every step along the way. Our culture is people-centered. People care here.”

Riverside went five whole years without an art teacher and lost their high school music teacher in 2022. Luckily, they had an uber-talented substitute teacher named Cherry Plagmann who was willing to go through the Transitional Certification Program (TCP) at UNK to fill the void.

“I never thought I would go back to college, I’ll tell you that,” laughed Plagmann, who held Bachelor of Fine Arts and Masters of Fine Arts degrees when she started subbing in the spring of 2022. “I was done with that. But my two children are here and they had just gotten started in school, so that was a big pull. And just the fact that they hadn’t had an art teacher for so long, it influenced me to say ‘Yes, I’ll do it so the kids don’t lose it.’ I love art, and didn’t want them to miss out on that.”

This isn’t where Plagmann envisioned herself when her family moved to the area 11 years ago, but, given the gift of hindsight, there’s nowhere else she’d rather be.

“We’re always looking to improve upon things, which I think is great,” she said. “If you think you have it all figured out, you can kind of get stuck in that. It’s good to have so many towns blended together. The fact that they have figured out a creative way to combine themselves together really benefits everybody.”

Amber Prososki is another Riverside educator who didn’t travel a “traditional” path to the profession. The first grade teacher grew up in St. Edward, some 20 miles down the road, and used her bachelor’s degree in social service counseling to forge a decade-long career working with foster families. When her daughter was diagnosed with dyslexia, she took some time off from work to learn as much about the condition as she could.

“I started working as a para in the kindergarten room right across from where my classroom is now, and that’s when I decided I wanted to be a teacher,” Prososki, who learned a great deal from kindergarten teacher Meridee Heikes, said. “That first year in the classroom, I was exhausted. I would go home every day and immediately take a nap. The kids were so wild and rambunctious, and I would just watch Mrs. Heikes be so patient and gentle with them and marvel. It was inspiring, and I completely fell in love with it.”

Riverside’s reputation attracted the Prososki family, and she said the culture has been everything it was cracked up to be.

“I’d say I expected to love it, and I truly do,” she said of teaching first-grade. “We have a family-like culture. The staff is incredible. I love the people I get to work with so much. There is a lot of pride here.”

She’d never accept the credit, but Kaczor, the six homegrown educators would agree, is the tie that binds. She was here for the merger and participated in no less than 80 special meetings that year. Unafraid to find talent in non-traditional places, Kaczor gained a total appreciation for how unique a district Riverside is when she spent four years away working at UNL.

“You don’t realize how special something is until you’re away from it,” Kaczor said. “I love the university and I loved living in Lincoln, but there was just something about that family feeling, how everybody’s all in every day and gives it their all, that left a hole. I love it here. I love how after school a lot of us will hang out and catch up on life. It’s rare. And I think parents see that and appreciate that. For these teachers, these kids are their kids too. It’s not just a job. It’s truly a career, 24/7, and I would say we’re very fortunate to have staff that have bought into that and believe in that.”

In fact, that’s the first thing Martinsen wants parents and families to know, she explained. No matter where her students come from, when they walk in those doors, they’re in a place they belong.

“What I want for my own children is what I want for everybody else’s children,” Martinsen said. “That is really the core value of a lot of the teachers that are in our district. They really feel that way, and a lot of our teachers have connections to this area, which is so neat.”

When Kaczor was gone, the culture she’d helped to build endured, but her absence was noticeable.

“The atmosphere just wasn’t as warm,” said Rankin. “When she walks down the hall, she’s singing Christmas Carols and saying hello to everybody she sees. She’s never too busy to answer your questions and she’s always approachable.”

Schools are the cornerstones of communities. In its 10th year of operations, Riverside Public Schools and its staff feel fortunate to be the cornerstone of four small towns in north-central Nebraska.

“We are Riverside, and we have embraced that,” said Weltruski. “We’ve blended the traditions of the two original schools while encouraging our kids to take ownership of Riverside and to start some special new traditions of their own.”

A decade can sure fly by in a flash, and, around here, they’re wasting no time.

They Said It!

Q: How do you want your students to remember their time here at Riverside?

Amber Prososki: I want them to know that they are smart and capable of anything. That’s what I want every kid to know by the time they leave my room. They’re just awesome.

Melissa Weltruski: Of course, the academics are important, but I want them to know Riverside as a place where they were truly cared for and allowed them to explore their interests. I want them to know it was a kind, caring and safe place that set them up for whatever path life takes them.

Tricia Martinsen: I know as an administrator I should say something like, ‘Oh, I had the greatest education and I remember the academics,’ but I really want them to look back on and say, ‘I walked in there and I was loved. Laughing was just as important as learning.’ It should be about growth. My biggest thing is wanting to see the kids grow academically, socially, emotionally, just in every way.

Stephanie Kaczor: We tell them all the time that we love them. We make mistakes. We’re here to guide them and to help them. We’re always here for them, we always love them, and we’re always just a phone call away. We stress relationships, relationships, relationships. And with every kid that relationship is different, but we want them to know we’re a safe and trusting adult, and they can always come back and we will do whatever we can to help them.

Kim Webb: That Mrs. Webb pushed me for a reason. I work with some of the kids with the most learning challenges, and you don’t want to push them past their limit. You don’t want them to not like you. You want them to look back and say, ‘Gosh, I’m glad she made me do that. I’m glad she pushed me, because yes, I can do it.’

Cherry Plagmann: I want them to remember feeling comfortable in my class and welcomed. I just want them to remember that they belonged. I had not done music since I was in high school. So to pick that back up and realize that it was still something that I enjoyed, that was neat. So I want them to take those skills and use them later in life, even if it’s not something that they do right away.

Q: Schools are nostalgic places, and that’s probably even more true for those of you who are alums. Do those waves of nostalgia ever wash over you?

Kim Webb: Absolutely. Because of my job, I’m in several rooms all day long, and every time I walk into the reading and English room upstairs I just remember the windows being open and it was freezing cold. That’s where I had French in junior high, and my teacher always had the windows open in the middle of the winter, because it was cold in France in the winter, he would explain with a laugh. Every room brings a memory. I can remember my business room, my fourth and fifth and sixth grade rooms. Definitely.

Tricia Martinsen: It’s very nostalgic for me. In my interview I was so passionate about getting this job that I shed tears. This was a really great and safe place for me. When I walk into the gymnasium, it takes me back to when I played here and when I coached here. It takes me back to watching my brothers and sisters play in there and then my children playing in there. When I walk down by the science room, I remember dissecting a pig. You don’t forget those kinds of things. I made so many memories here.

Q: You have a unique collection of homegrown teaching talent here. How is that network of people who entered the profession in a similar fashion valuable to you?

Amber Prososki: It definitely helps having people to bounce things off of. We share a similar buy-in. We did this later in life, and when you do something like this later in life it means you really want to do it. We have amazing paras and I like the fact that I’ve worked in that position because it allows me to be able to see both perspectives. We’re a small school, so we all have to help each other out. We’re striving to grow and reach higher benchmarks. It’s an exciting place to be.

Cherry Plagmann: That network is so important. It can be hard to come into a small town not having grown up here because you don’t have those same connections or relatives like others do. So having those people is a nice resource and helps you gain a sense of the community and its culture.

Julie Rankin: That’s so important. We collaborate and try to solve problems together. People are always willing to step in if they know you’re having a tough time with a student or life in general, and you’d do the same for them.

Kim Webb: I lean on them. They lean on me. We have to collaborate daily, sometimes hourly. I remember being in fifth and sixth grade and Julie would come down from high school and practice her speeches, and now we’re working together.

Q: This district seems forward thinking and innovative, certainly in the way it fills open teaching positions. Tell me about Stephanie and the leadership of this district.

Tricia Martinsen: I don’t know if I would be where I am today without her and the examples and models she set. The kids know her by name. If I’m not here, they go to her. And sometimes when they know they’re not going to get their way with me, they still go to her to see if they can get their way. She is the reason this school moves the way it does. She’s not only a role model, but we have been friends for 25 years.

Cherry Plagmann: We wouldn’t be here teaching if they weren’t creative. I think it’s very serendipitous that all of those blocks lined up, but takes one person to kick a block and have it not happen at all. Going out of their way to say, ‘We’re going to do this, and we’re going to take a chance on you’, that just means a lot.